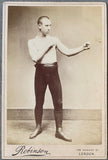

BURGE, DICK ORIGINAL CABINET CARD

JO Sports Inc.

Regular price $300.00

Dick Burge, born in 1865 in south west England near the rough-and-tumble port city of Bristol, had 22 fights that would find their way into the record books. In these matches, he was 12-7-2 with one “no contest.” Several of these fights had a bad odor about them. Suspicious fights were endemic in his era where a boxer’s earnings were often hitched to the outcome of bets. The victorious boxer got a piece of his backer’s winnings and perhaps a gratuity from others that profited from his triumph; the loser got nothing unless he worked out some deal to insure he wouldn’t go home empty-handed. A 12-7-2 record is hardly the template of an important prizefighter, but Dick Burge was very important. Three thousand people reportedly turned out for his funeral. The King and Queen sent a sympathy card to his widow, Bella. Burge’s first sport was pedestrianism (long-distance race walking). Prizefights in Burge’s days were sometimes contested for hours; no fighter advanced far without great stamina and long-distance running was a common gateway into the world of the prize ring. For a time he worked as a booth fighter for a traveling circus, taking on all comers although his opponent was more likely to be a confederate planted in the audience. On the fair circuit Burge caught the attention of someone with deep pockets and he was soon pitted against boxers whose names resonated with the sporting crowd. In 1891, in his eighth documented fight, he was matched against Jem Carney in a 20-round contest billed for the world lightweight title. The bout, contested under Queensberry rules, was held on the trading floor of the Hop and Malt Exchange in the Southwark borough of London. The match ended in the 11th round when the referee awarded the fight to Burge on a foul. The term “world title” was thrown around loosely in those days, but Burge had a legitimate claim to it in that Carney had previously fought the great Jack McAuliffe to a standstill. Contested under London Prize Ring rules (a round ended when a fighter was knocked down or went to the turf of his own accord to catch a breather), the Carney-McAuliffe fight at Revere Beach, Massachusetts, went on for several hours before McAuliffe’s partisans charged the ring to break up the fight, ostensibly to save their bets. A British Empire title actually carried more cachet in Great Britain as this badge of honor had a less muddled lineage. Burge claimed this diadem in 1894 with a hard-fought win over “Cast Iron” Harry Nickless (Burge knocked him out in the twenty-eighth round) and defended it eight months later with a third round stoppage of Australia’s Tom Williams at the National Sporting Club. These matches were contested at 140 pounds. The lightweight ceiling wasn’t yet firmly fixed. For a British boxer, nothing matched the prestige of appearing in the featured bout at the National Sporting Club. Located in the fashionable Covent Garden district of London, the exclusive men’s club, founded in 1891, hosted a string of internationally important prizefights. They were held in the basement theater where patrons in evening clothes were discouraged from shouting. It was here that Dick Burge had his most highly anticipated match, opposing George Lavigne, the Saginaw Kid. Contested on June 1, 1896, at 138 pounds, this was a true world lightweight title fight as it was acknowledged as such on both sides of the Atlantic. Lavigne, who stood only five-foot-three-and-a half, four inches shorter than Burge, was teak tough. He swarmed all over Burge from the opening bell and eventually wore him down. The referee halted the fray in the seventeenth round. But Burge, who spent the better part of the day in a sauna to make weight, fought gallantly. A reporter for London’s Pall Mall Gazette wrote that it was the best fight ever staged there. The SRO crowd included a smattering of big gamblers from New York including the city’s political kingmaker Richard Croker, the Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall. Burge fought sporadically over the next four-and-a-half years, winning some and losing some. His last bout came on Jan. 28, 1901, against Jerry Driscoll, a middleweight of some repute. It was a no-holds-barred embroilment although it wasn’t intended that way. The referee, unable to get the fighters to heed his commands, left the premises after the second round and the fight wasn’t resumed, much to the disgust of the crowd. This was a sad way to end a career studded with many exhilarating moments, but the worst was yet to come for Dick Burge. Before the year was out, he was entangled in the sordid Goudie Affair, a sensational scandal that attracted international press coverage. Thomas Goudie worked as a bookkeeper for the Bank of Liverpool. A bachelor, he rented a flat in a boardinghouse and had very few friends. In his mid-twenties, he acquired an interest in horseracing. In the spring of 1901, traveling by train to a race meet, he was drawn into a friendly game of cards by two racetrack touts who talked big, boasting of big scores born of inside information. Goudie was more than a little intrigued and was induced to wire them money which they would place for him whenever he was notified that they had a sure thing. Word got around that the sharpies had found a live one and eventually others of the same ilk were able to horn in on the action. You can guess where this is headed. Those sure things routinely finished out of the money and to recoup his losses Goudie began forging checks. He kept the ledger for the bank’s biggest depositor, a soap manufacturer, and from this man’s account he embezzled almost $170,000. The leakage made it the largest recorded embezzlement in the annals of British banking. Where did Burge fit in? After Goudie’s arrest, Burge was one of five people indicted for fostering the scam. His exact role was complicated. Like the others, he was hit with an array of charges, some of which stuck and some of which didn’t. It is a fact that some of the missing money found its way into Burge’s bank account. Two of the alleged conspirators disappeared before they could be brought to trial. Burge and Goudie received the harshest sentences. Each was sentenced to ten years of penal servitude. Burge was released after seven years. Thomas Goudie, the mild-mannered bank clerk, died in prison at age thirty-four. His death was attributed to a heart ailment, but the root cause was said to be a broken spirit. After his release from prison, Burge acquired the abandoned Surrey Chapel, fixed it up, re-named it The Ring, and turned it into London’s busiest boxing arena. The odd, round-shaped building (supposedly built without four corners so that the devil wouldn’t have a corner in which to hide), which dated to 1783, sat in what was then a tough district of the city, Blackfriars. The fights attracted some unsavory characters — a man known as Jack Spot, a regular attendee, was the collector of last resort for loan sharks — but there were very few incidents. In a stroke of genius, Burge hired a local minister, Rev. Thomas Collins, as his timekeeper. His mere presence, said a reporter, inspired confidence in the integrity of the bouts and caused patrons to tone down their blue language. Burge also barred bookmakers from accepting wagers at ringside. In his fighting days Burge engaged in a number of suspicious fights, but he brooked none of that in his own establishment. It seemed, however, that Burge could never erase the stain of the Goudie Affair. In the papers, he was repeatedly referenced as an ex-convict. Then came World War I and Burge rose to the occasion. Between May 1915 and May 1918, London came under attack from German zeppelin and other kinds of German aircraft. The death toll was set at 557, roughly three times that number were injured, and more than 300,000 left their homes to seek shelter in an underground railway station. Burge pitched in by promoting benefit shows for the families of soldiers at the front lines, but he did more than that. Although he had reached the age of 50, he enlisted in the Surrey Regiment where he was assigned to the ambulance corps. Working a long shift on a wet and chilly night with Red Cross medics, Burge caught pneumonia. He died shortly thereafter. The turnout at his funeral bore evidence that by his selfless deeds he had lifted the black cloud that had hovered over him. Lore has it that the head of Scotland Yard was among those that came to pay their respects. By the way, after Dick Burge’s death in March of 1918, his widow Bella, a former music hall entertainer, kept The Ring going. Boxing continued there until 1939 when the building was closed for renovations. It would never re-open. Damaged in a German air raid in 1940, it was reduced to rubble the following year when it absorbed a direct hit from another German bomber. Offered here is an original cabinet card photo of Dick Burge.

FULL DESCRIPTION: This is an original cabinet card photo of Dick Burge in full fight pose as he looked at the height of his boxing career. Photographer stamp for Robinson of London on the front mount and on the back. Dick Burge identified on the back in pencil. Bold, clear image. Not creased or torn. Clean front and back. Minor corner wear. 4 1/4" x 6 1/2." Rare, the first we have offered.

Size: 4 1/4" x 6 1/2"

Condition: Excellent